Hans Pfitzner on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

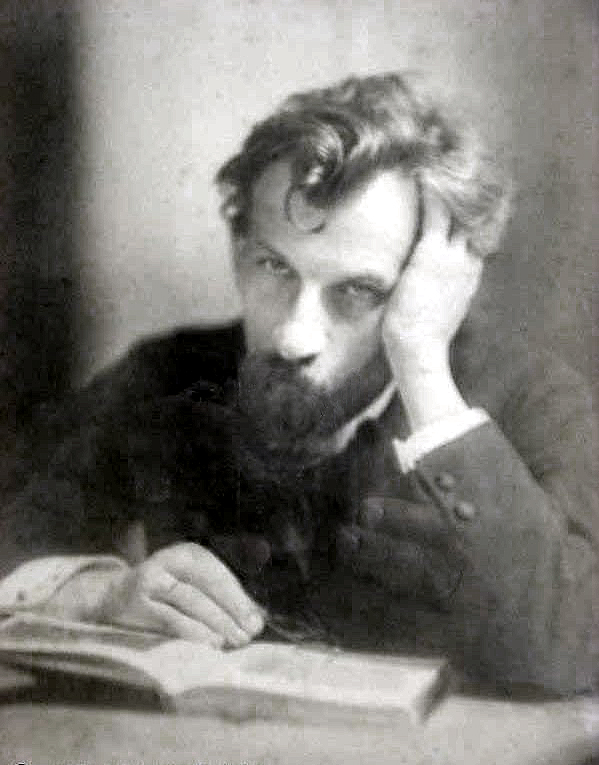

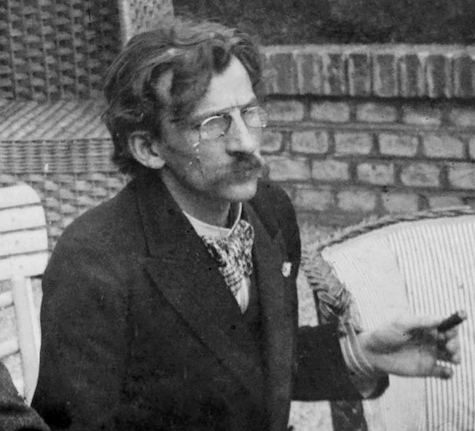

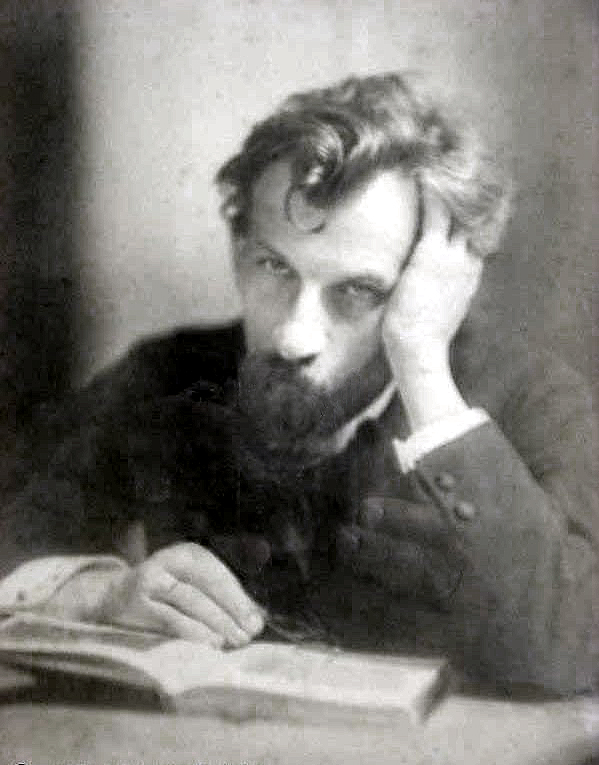

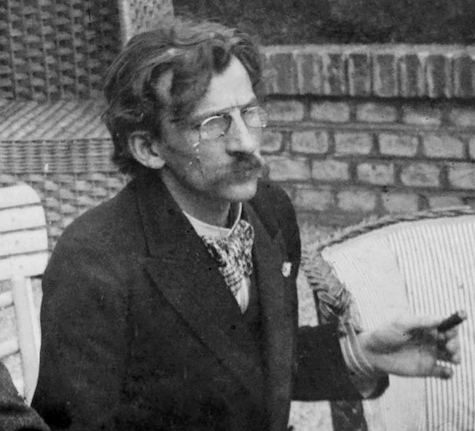

Hans Erich Pfitzner (5 May 1869 – 22 May 1949) was a German composer, conductor and polemicist who was a self-described anti-

Hans Erich Pfitzner (5 May 1869 – 22 May 1949) was a German composer, conductor and polemicist who was a self-described anti-

Easily the most celebrated of Pfitzner's prose works is his pamphlet ''Futuristengefahr'' ("Danger of Futurists"), written in response to

Easily the most celebrated of Pfitzner's prose works is his pamphlet ''Futuristengefahr'' ("Danger of Futurists"), written in response to

Pfitzner's home having been destroyed in the war by Allied bombing, and his membership in the Munich Academy of Music having been revoked for his speaking out against Nazism, the composer in 1945 found himself homeless and mentally ill. But after the war he was denazified and re-pensioned, performance bans were lifted and he was granted residence in the old people's home in

Pfitzner's home having been destroyed in the war by Allied bombing, and his membership in the Munich Academy of Music having been revoked for his speaking out against Nazism, the composer in 1945 found himself homeless and mentally ill. But after the war he was denazified and re-pensioned, performance bans were lifted and he was granted residence in the old people's home in

Pfitzner's music—including pieces in all the major genres except the symphonic poem—was respected by contemporaries such as

Pfitzner's music—including pieces in all the major genres except the symphonic poem—was respected by contemporaries such as

UbuWeb:A New Musical Reality": Futurism, Modernism, and "The Art of Noises"

by Robert P. Morgan * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Pfitzner, Hans 1869 births 1949 deaths Burials at the Vienna Central Cemetery German male conductors (music) German male classical composers German opera composers German Romantic composers Hoch Conservatory alumni Male opera composers Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) 20th-century German conductors (music) 20th-century German male musicians 19th-century German male musicians Pupils of Iwan Knorr

Hans Erich Pfitzner (5 May 1869 – 22 May 1949) was a German composer, conductor and polemicist who was a self-described anti-

Hans Erich Pfitzner (5 May 1869 – 22 May 1949) was a German composer, conductor and polemicist who was a self-described anti-modernist

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

. His best known work is the post-Romantic

Post-romanticism or Postromanticism refers to a range of cultural endeavors and attitudes emerging in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, after the period of Romanticism.

Post-romanticism in literature

The period of post-romantici ...

opera ''Palestrina

Palestrina (ancient ''Praeneste''; grc, Πραίνεστος, ''Prainestos'') is a modern Italian city and ''comune'' (municipality) with a population of about 22,000, in Lazio, about east of Rome. It is connected to the latter by the Via Pre ...

'' (1917), loosely based on the life of the sixteenth-century composer Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina ( – 2 February 1594) was an Italian composer of late Renaissance music. The central representative of the Roman School, with Orlande de Lassus and Tomás Luis de Victoria, Palestrina is considered the leading ...

and his ''Missa Papae Marcelli

''Missa Papae Marcelli'', or ''Pope Marcellus Mass'', is a mass ''sine nomine'' by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina. It is his best-known mass, and is regarded as an archetypal example of the complex polyphony championed by Palestrina. It was sung ...

''.

Life

Pfitzner was born in Moscow where his father played cello in a theater orchestra. The family returned to his father's native townFrankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , "Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on its na ...

in 1872, when Pfitzner was two years old, he always considered Frankfurt his home town. He received early instruction in violin from his father, and his earliest compositions were composed at age 11. In 1884 he wrote his first songs. From 1886 to 1890 he studied composition with Iwan Knorr

Iwan Otto Armand Knorr (3 January 1853 – 22 January 1916) was a German composer and music teacher.

Life

A native of Gniew, he attended the Leipzig Conservatory where he studied with Ignaz Moscheles, Ernst Friedrich Richter and Carl Reinecke. I ...

and piano with James Kwast

James Kwast (23 November 185231 October 1927) was a Dutch-German pianist and renowned teacher of many other notable pianists. He was also a minor composer and editor.

Biography

Jacob James Kwast was born in Nijkerk, Netherlands, in 1852. After ...

at the Hoch Conservatory

Dr. Hoch's Konservatorium – Musikakademie was founded in Frankfurt am Main on 22 September 1878. Through the generosity of Frankfurter Joseph Hoch, who bequeathed the Conservatory one million German gold marks in his testament, a school for ...

in Frankfurt. (He later married Kwast's daughter Mimi Kwast, a granddaughter of Ferdinand Hiller

Ferdinand (von) Hiller (24 October 1811 – 11 May 1885) was a German composer, conductor, pianist, writer and music director.

Biography

Ferdinand Hiller was born to a wealthy Jewish family in Frankfurt am Main, where his father Justus (orig ...

, after she had rejected the advances of Percy Grainger

Percy Aldridge Grainger (born George Percy Grainger; 8 July 188220 February 1961) was an Australian-born composer, arranger and pianist who lived in the United States from 1914 and became an American citizen in 1918. In the course of a long an ...

.) He taught piano and theory at the Koblenz

Koblenz (; Moselle Franconian language, Moselle Franconian: ''Kowelenz''), spelled Coblenz before 1926, is a German city on the banks of the Rhine and the Moselle, a multi-nation tributary.

Koblenz was established as a Roman Empire, Roman mili ...

Conservatory from 1892 to 1893. In 1894 he was appointed conductor at the Staatstheater Mainz where he worked for a few months. These were all low-paying jobs, and Pfitzner was working as Erster (First) Kapellmeister

(, also , ) from German ''Kapelle'' (chapel) and ''Meister'' (master)'','' literally "master of the chapel choir" designates the leader of an ensemble of musicians. Originally used to refer to somebody in charge of music in a chapel, the term ha ...

with the Berlin Theater des Westens

The Theater des Westens (Theatre of the West) is one of the most famous theatres for musicals and operettas in Berlin, Germany, located at 10–12 in Charlottenburg. It was founded in 1895 for plays. The present house was opened in 1896 and de ...

when he was appointed to a modestly prestigious post of opera director and head of the conservatory in Straßburg (Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label=Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label=Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the Eu ...

) in 1908, when Pfitzner was almost 40.

In Strasbourg, Pfitzner finally had some professional stability, and it was there he gained significant power to direct his own operas. He viewed control over the stage direction to be his particular domain, and this view was to cause him particular difficulty for the rest of his career. The central event of Pfitzner's life was the annexation of Imperial Alsace

Alsace (, ; ; Low Alemannic German/ gsw-FR, Elsàss ; german: Elsass ; la, Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In 2020, it had ...

—and with it Strasbourg— by France in the aftermath of World War I. Pfitzner lost his livelihood and was left destitute at age 50. This hardened several difficult traits in Pfitzner's personality: an elitism believing he was entitled to sinecures for his contributions to German art and for the hard work of his youth, notorious social awkwardness and a lack of tact, a sincere belief that his music was under-recognized and under-appreciated with a tendency for his sympathizers to form cults around him, a patronizing style with his publishers, and a feeling that he had been personally slighted by Germany's enemies.Michael Kater, ''Composers of the Nazi Era: Eight Portraits'' (NY: Oxford University Press, 2000), 144–182, esp. 146, 160, His bitterness and cultural pessimism deepened in the 1920s with the death of his wife in 1926 and with meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Other symptoms include confusion or ...

affecting his older son Paul, who was committed to institutionalized medical care.

In 1895, Richard Bruno Heydrich

Richard Bruno Heydrich (23 February 1865 – 24 August 1938) was a German opera singer (tenor), composer, and founder of the Halle Conservatory. A talented musician since childhood, Heydrich would find great success as a musical teacher, through ...

sang the title role in the premiere of people like Hans Pfitzner's first opera, ''Der arme Heinrich'', based on the poem of the same name by Hartmann von Aue

Hartmann von Aue, also known as Hartmann von Ouwe, (born ''c.'' 1160–70, died ''c.'' 1210–20) was a German knight and poet. With his works including ''Erec'', ''Iwein'', '' Gregorius'', and ''Der arme Heinrich'', he introduced the Arthuria ...

. More to the point, Heydrich "saved" the opera. Pfitzner's ''magnum opus'' was ''Palestrina

Palestrina (ancient ''Praeneste''; grc, Πραίνεστος, ''Prainestos'') is a modern Italian city and ''comune'' (municipality) with a population of about 22,000, in Lazio, about east of Rome. It is connected to the latter by the Via Pre ...

'', which had its premiere in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the States of Germany, German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the List of cities in Germany by popu ...

on 12 June 1917 under the baton of Jewish conductor Bruno Walter

Bruno Walter (born Bruno Schlesinger, September 15, 1876February 17, 1962) was a German-born conductor, pianist and composer. Born in Berlin, he escaped Nazi Germany in 1933, was naturalised as a French citizen in 1938, and settled in the Un ...

. On the day before he died in February 1962, Walter dictated his last letter, which ended ''"Despite all the dark experiences of today I am still confident that ''Palestrina'' will remain. The work has all the elements of immortality"''.

Easily the most celebrated of Pfitzner's prose works is his pamphlet ''Futuristengefahr'' ("Danger of Futurists"), written in response to

Easily the most celebrated of Pfitzner's prose works is his pamphlet ''Futuristengefahr'' ("Danger of Futurists"), written in response to Ferruccio Busoni

Ferruccio Busoni (1 April 1866 – 27 July 1924) was an Italian composer, pianist, conductor, editor, writer, and teacher. His international career and reputation led him to work closely with many of the leading musicians, artists and literary ...

's ''Sketch for a New Aesthetic of Music''. "Busoni," Pfitzner complained, "places all his hopes for Western music in the future and understands the present and past as a faltering beginning, as the preparation. But what if it were otherwise? What if we find ourselves presently at a high point, or even that we have already passed beyond it?" Pfitzner had a similar debate with the critic Paul Bekker

Max Paul Eugen Bekker (11 September 1882 – 7 March 1937) was a German music critic and author. Described as having "brilliant style and ..extensive theoretical and practical knowledge," Bekker was chief music critic for both the '' Frankfu ...

.

Pfitzner dedicated his Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 34 (1923) to the Australian violinist Alma Moodie

Alma Mary Templeton Moodie (12 September 18987 March 1943) was an Australian violinist who established an excellent reputation in Germany in the 1920s and 1930s. She was regarded as the foremost female violinist during the inter-war years, and s ...

. She premiered it in Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

on 4 June 1924, with the composer conducting. Moodie became its leading exponent, and performed it over 50 times in Germany with conductors such as Pfitzner, Wilhelm Furtwängler

Gustav Heinrich Ernst Martin Wilhelm Furtwängler ( , , ; 25 January 188630 November 1954) was a German conductor and composer. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest symphonic and operatic conductors of the 20th century. He was a major ...

, Hans Knappertsbusch

Hans Knappertsbusch (12 March 1888 – 25 October 1965) was a German conductor, best known for his performances of the music of Wagner, Bruckner and Richard Strauss.

Knappertsbusch followed the traditional route for an aspiring conductor in Ger ...

, Hermann Scherchen, Karl Muck

Karl Muck (October 22, 1859 – March 3, 1940) was a German-born conductor of Classical music. He based his activities principally in Europe and mostly in opera. His American career comprised two stints at the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO). M ...

, Carl Schuricht

Carl Adolph Schuricht (; 3 July 18807 January 1967) was a German conductor.

Life and career

Schuricht was born in Danzig (Gdańsk), German Empire; his father's family had been respected organ-builders. His mother, Amanda Wusinowska, a widow soo ...

, and Fritz Busch

Fritz Busch (13 March 1890 – 14 September 1951) was a German conductor.

Busch was born in Siegen, Westphalia, to a musical family, and studied at the Cologne Conservatory. After army service in the First World War, he was appointed to senior p ...

. At that time, the Pfitzner concerto was considered the most important addition to the violin concerto repertoire since the first concerto of Max Bruch

Max Bruch (6 January 1838 – 2 October 1920) was a German Romantic composer, violinist, teacher, and conductor who wrote more than 200 works, including three violin concertos, the first of which has become a prominent staple of the standard ...

(1866), although it is not played by most violinists these days. On one occasion in 1927, conductor Peter Raabe

Peter Raabe (27 November 1872 – 12 April 1945) was a German composer and conductor.

Biography

Raabe graduated from 3 schools: the Higher Musical School in Berlin; and the universities of Munich; and Jena. In 1894–98 Raabe worked in König ...

programmed the concerto for public broadcast and performance in Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th- ...

but did not budget for copying of the sheet music; as a result, the work was "withdrawn" at the last minute and replaced with the familiar Brahms concerto.

The Nazi era

Increasingly nationalistic in his middle and old age, Pfitzner was at first regarded sympathetically by important figures inNazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, in particular by Hans Frank

Hans Michael Frank (23 May 1900 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and lawyer who served as head of the General Government in Nazi-occupied Poland during the Second World War.

Frank was an early member of the German Workers' Party ...

, with whom he remained on good terms. But he soon fell out with chief Nazis, who were alienated by his long musical association with the Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

conductor Bruno Walter. He incurred extra wrath from the Nazis by refusing to obey the regime's request to provide incidental music to Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's ''A Midsummer Night's Dream

''A Midsummer Night's Dream'' is a comedy written by William Shakespeare 1595 or 1596. The play is set in Athens, and consists of several subplots that revolve around the marriage of Theseus and Hippolyta. One subplot involves a conflict amon ...

'' that could be used in place of the famous setting by Felix Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include sy ...

, unacceptable to the Nazis because of his Jewish origin. Pfitzner maintained that Mendelssohn's original was far better than anything he himself could offer as a substitute.

As early as 1923, Pfitzner and Hitler met. It was while the former was a hospital patient: Pfitzner had undergone a gall bladder

In vertebrates, the gallbladder, also known as the cholecyst, is a small hollow organ where bile is stored and concentrated before it is released into the small intestine. In humans, the pear-shaped gallbladder lies beneath the liver, although ...

operation when Anton Drexler

Anton Drexler (13 June 1884 – 24 February 1942) was a German far-right political agitator for the Völkisch movement in the 1920s. He founded the pan-German and anti-Semitic German Workers' Party (DAP), the antecedent of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) ...

, who knew both men well, arranged a visit. Hitler did most of the talking, but Pfitzner dared to contradict him regarding the homosexual and antisemitic thinker Otto Weininger

Otto Weininger (; 3 April 1880 – 4 October 1903) was an Austrian philosopher who lived in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In 1903, he published the book ''Geschlecht und Charakter'' (''Sex and Character''), which gained popularity after his suici ...

, causing Hitler to leave in a huff. Later on, Hitler told Nazi cultural architect Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head o ...

that he wanted "nothing further to do with this Jewish rabbi." Pfitzner, unaware of this comment, believed Hitler to be sympathetic to him.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Rosenberg recruited Pfitzner, a notoriously bad speaker, to lecture for the Militant League for German Culture

The English word ''militant'' is both an adjective and a noun, and it is generally used to mean vigorously active, combative and/or aggressive, especially in support of a cause, as in "militant reformers". It comes from the 15th century Latin ...

(''Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur'') that same year and Pfitzner accepted, hoping it would help him find an influential position. Hitler, however, saw to it that the composer was passed over in favor of party hacks for positions as opera director in Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf ( , , ; often in English sources; Low Franconian and Ripuarian: ''Düsseldörp'' ; archaic nl, Dusseldorp ) is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in th ...

and ''Generalintendant'' of the Berlin Municipal Opera, despite hints from authorities that both positions were being held for him.

Very early in Hitler's rule, Pfitzner received an injunction from Hans Frank (by this time Justice Minister in Bavaria) and Wilhelm Frick

Wilhelm Frick (12 March 1877 – 16 October 1946) was a prominent German politician of the Nazi Party (NSDAP), who served as Reich Minister of the Interior in Adolf Hitler's cabinet from 1933 to 1943 and as the last governor of the Protectorate ...

(Interior Minister in Hitler's own cabinet) against traveling to the Salzburg Festival in 1933 to conduct his violin concerto. Pfitzner had managed to gain a stable conducting contract from the Munich opera in 1928, but ran into demeaning treatment from chief conductor Hans Knappertsbusch

Hans Knappertsbusch (12 March 1888 – 25 October 1965) was a German conductor, best known for his performances of the music of Wagner, Bruckner and Richard Strauss.

Knappertsbusch followed the traditional route for an aspiring conductor in Ger ...

and from the opera house's intendant, a man named Franckenstein.

In 1934 Pfitzner was forced into retirement and lost his positions as opera conductor, stage director and academy professor. He was also given a minimal pension of a few hundred marks a month, which he contested until 1937 when Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

resolved the issue. For a Nazi party rally in 1934, Pfitzner had hopes of being allowed to conduct; but he was rejected for the role, and at the rally himself he learned for the first time that Hitler considered him to be half-Jewish. Nor was Hitler the first person to suppose this. Winifred Wagner

Winifred Marjorie Wagner ( Williams; 23 June 1897 – 5 March 1980) was the English-born wife of Siegfried Wagner, the son of Richard Wagner, and ran the Bayreuth Festival after her husband's death in 1930 until the end of World War II in 1 ...

, the director of the Bayreuth Festival

The Bayreuth Festival (german: link=no, Bayreuther Festspiele) is a music festival held annually in Bayreuth, Germany, at which performances of operas by the 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner are presented. Wagner himself conceived ...

and a confidante of Hitler, also believed it. Pfitzner was forced to prove that he had, in fact, totally Gentile ancestry. By 1939 he had grown thoroughly disenchanted with the Nazi regime, except for Frank, whom he continued to respect.

Pfitzner's views on "the Jewish Question

The Jewish question, also referred to as the Jewish problem, was a wide-ranging debate in 19th- and 20th-century European society that pertained to the appropriate status and treatment of Jews. The debate, which was similar to other " national ...

" were both contradictory and illogical. He viewed Jewishness as a cultural trait rather than a racial one. A 1930 statement that caused difficulty for him in the pension affair was that although Jewry might pose "dangers to German spiritual life and German Kultur," many Jews had done a lot for Germany and that antisemitism ''per se'' was to be condemned. He was willing to make exceptions to a general policy of antisemitism. For example, he recommended the performance of Marschner

Heinrich August Marschner (16 August 1795 – 14 December 1861) was the most important composer of German opera between Carl Maria von Weber, Weber and Richard Wagner, Wagner.Der Templer und die Jüdin

''Der Templer und die Jüdin '' (English: ''The Templar and the Jewess'') is an opera (designated as a '' Große romantische Oper'') in three acts by Heinrich Marschner. The German libretto by Wilhelm August Wohlbrück was based on a number of int ...

'' based on Scott's ''Ivanhoe

''Ivanhoe: A Romance'' () by Walter Scott is a historical novel published in three volumes, in 1819, as one of the Waverley novels. Set in England in the Middle Ages, this novel marked a shift away from Scott’s prior practice of setting st ...

'', protected his Jewish pupil Felix Wolfes

Felix Wolfes (September 2, 1892 in Hannover – March 28, 1971 in Boston) was an American educator, Conducting, conductor and composer.''Baker's Biographical Dictionary'', eighth edition, p. 2068

Biography

Felix was born to Jewish parents in Hanno ...

of Cologne, along with conductor Furtwängler aided the young conductor Hans Schwieger, who had a Jewish wife, and maintained his friendship with Bruno Walter and especially his childhood journalist friend Paul Cossman, a "self-loathing" non-practicing Jew who was incarcerated in 1933.

The attempts which Pfitzner made on behalf of Cossman might have caused Gestapo chief Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich ( ; ; 7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a high-ranking German SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust.

He was chief of the Reich Security Main Office (inclu ...

, incidentally the son of the heldentenor

A heldentenor (; English: ''heroic tenor''), earlier called tenorbariton, is an operatic tenor voice, most often associated with Wagnerian repertoire.

It is distinct from other tenor ''fächer'' by its endurance, volume, and dark timbre, which ...

who premiered Pfitzner's first opera, to investigate him. Pfitzner's petitions probably contributed to Cossman's release in 1934, although he was eventually re-arrested in 1942 and died of dysentery in Theresienstadt

Theresienstadt Ghetto was established by the SS during World War II in the fortress town of Terezín, in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia ( German-occupied Czechoslovakia). Theresienstadt served as a waystation to the extermination ca ...

. In 1938, Pfitzner joked that he was afraid to see a celebrated eye doctor in Munich because "his great-grandmother had once observed a quarter-Jew crossing the street." He worked with Jewish musicians throughout his career. In the early thirties he often accompanied famed contralto

A contralto () is a type of classical female singing voice whose vocal range is the lowest female voice type.

The contralto's vocal range is fairly rare; similar to the mezzo-soprano, and almost identical to that of a countertenor, typically b ...

Ottilie Metzger-Lattermann, later murdered in Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

, in recitals and had dedicated his four songs, Op. 19, to her as early as 1905. He had dedicated his songs, Op. 24, to Jewish critic and Jewish cultural society founder Arthur Eloesser in 1909. Still, Pfitzner maintained close contact with virulent antisemites like music critics Walter Abendroth Walter Fedor Georg Abendroth (29 May 1896 in Hanover – 30 September 1973 in Fischbachau) was a German composer, editor, and writer on music.

Life

Walter Abendroth was born in the Lower Saxon city of Hanover. The middle child of a land surveyo ...

and Victor Junk, and did not scruple to use antisemitic invective (common enough among people of his generation, and not just in Germany) to pursue certain aims.

Pfitzner's home having been destroyed in the war by Allied bombing, and his membership in the Munich Academy of Music having been revoked for his speaking out against Nazism, the composer in 1945 found himself homeless and mentally ill. But after the war he was denazified and re-pensioned, performance bans were lifted and he was granted residence in the old people's home in

Pfitzner's home having been destroyed in the war by Allied bombing, and his membership in the Munich Academy of Music having been revoked for his speaking out against Nazism, the composer in 1945 found himself homeless and mentally ill. But after the war he was denazified and re-pensioned, performance bans were lifted and he was granted residence in the old people's home in Salzburg

Salzburg (, ; literally "Salt-Castle"; bar, Soizbuag, label=Bavarian language, Austro-Bavarian) is the List of cities and towns in Austria, fourth-largest city in Austria. In 2020, it had a population of 156,872.

The town is on the site of the ...

. There, in 1949, he died. Furtwängler conducted a performance of his Symphony in C major at the Salzburg Festival with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

The Vienna Philharmonic (VPO; german: Wiener Philharmoniker, links=no) is an orchestra that was founded in 1842 and is considered to be one of the finest in the world.

The Vienna Philharmonic is based at the Musikverein in Vienna, Austria. Its ...

in the summer of 1949, just after the composer's death. Following long neglect, Pfitzner's music began to reappear in opera houses, concert halls and recording studios during the 1990s, including a controversial performance of the Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist si ...

production of ''Palestrina'' in Manhattan's Lincoln Center

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts (also simply known as Lincoln Center) is a complex of buildings in the Lincoln Square neighborhood on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. It has thirty indoor and outdoor facilities and is host to 5 millio ...

in 1997.

During the 1990s more and more musicologists, mainly German and British, began examining Pfitzner's life and work. Biographer Hans Peter Vogel wrote that Pfitzner was the only composer of the Nazi era who attempted to come to grips with National Socialism both intellectually and spiritually after 1945. In 2001, Sabine Busch examined the ideological tug-of-war of the composer's involvement with the National Socialists, based in part on previously unavailable material. She concluded that, although the composer was not exclusively pro-Nazi nor purely the antisemitic chauvinist often associated with his image, he engaged with Nazi powers who he thought would promote his music and became embittered when the Nazis found the "elitist old master's often morose music" to be "little propaganda-worthy." The most comprehensive English-language account of Pfitzner's relations with the Nazis is by Michael Kater.

Musical style and reception

Pfitzner's music—including pieces in all the major genres except the symphonic poem—was respected by contemporaries such as

Pfitzner's music—including pieces in all the major genres except the symphonic poem—was respected by contemporaries such as Gustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler (; 7 July 1860 – 18 May 1911) was an Austro-Bohemian Romantic composer, and one of the leading conductors of his generation. As a composer he acted as a bridge between the 19th-century Austro-German tradition and the modernism ...

and Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss (; 11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a German composer, conductor, pianist, and violinist. Considered a leading composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras, he has been described as a successor of Richard Wag ...

, although neither man cared much for Pfitzner's innately acerbic manner (and Alma Mahler

Alma Maria Mahler Gropius Werfel (born Alma Margaretha Maria Schindler; 31 August 1879 – 11 December 1964) was an Austrian composer, author, editor, and socialite. At 15, she was mentored by Max Burckhard. Musically active from her early yea ...

repaid his adoration with contempt, despite her agreement with his intuitive musical idealism, a fact evident in her letters to the wife of Alban Berg

Alban Maria Johannes Berg ( , ; 9 February 1885 – 24 December 1935) was an Austrian composer of the Second Viennese School. His compositional style combined Romantic lyricism with the twelve-tone technique. Although he left a relatively sma ...

). Although Pfitzner's music betrays Wagnerian influences, the composer was not attracted to Bayreuth, and was personally despised by Cosima Wagner

Francesca Gaetana Cosima Wagner ( née Liszt; 24 December 1837 – 1 April 1930) was the daughter of the Hungarian composer and pianist Franz Liszt and Franco-German romantic author Marie d'Agoult. She became the second wife of the German co ...

, in part because Pfitzner sought notice and recognition from such "anti-Wagnerian" composers as Max Bruch and Johannes Brahms.

Pfitzner's works combine Romantic and Late Romantic elements with extended thematic development, atmospheric music drama, and the intimacy of chamber music. Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

musicologist Walter Frisch has described Pfitzner as a "regressive modernist." His is a highly personal offshoot of the Classical/Romantic tradition as well as the conservative musical aesthetic and Pfitzner defended his style in his own writings. Particularly notable are Pfitzner's numerous and delicate lied

In Western classical music tradition, (, plural ; , plural , ) is a term for setting poetry to classical music to create a piece of polyphonic music. The term is used for any kind of song in contemporary German, but among English and French s ...

er, influenced by Hugo Wolf

Hugo Philipp Jacob Wolf (13 March 1860 – 22 February 1903) was an Austrian composer of Slovene origin, particularly noted for his art songs, or Lieder. He brought to this form a concentrated expressive intensity which was unique in late Ro ...

, yet with their own rather melancholy charm. Several of them were recorded during the 1930s by the distinguished baritone Gerhard Hüsch

Gerhard Heinrich Wilhelm Fritz Hüsch (2 February 190123 November 1984) was one of the most important German singers of modern times. A lyric baritone, he specialized in '' Lieder'' but also sang, to a lesser extent, German and Italian opera ...

, with the composer at the piano. His first symphony—the Symphony in C-sharp minor—underwent a strange genesis: it was not conceived in orchestral terms at all, but was a reworking of a string quartet. The works betray a late pious inspiration and although they take on a late Romantic qualities, they show others associated with the brooding unwieldiness of a modern idiom. For example, composer Arthur Honegger

Arthur Honegger (; 10 March 1892 – 27 November 1955) was a Swiss composer who was born in France and lived a large part of his life in Paris. A member of Les Six, his best known work is probably ''Antigone'', composed between 1924 and 1927 to ...

writes in 1955, after criticizing too much polyphony and overly long orchestral writing in a long essay devoted to ''Palestrina'',

Musically, the work shows a superior design, which demands respect. The themes are clearly formed, which makes it easy to follow...Pfitzner's work was appreciated by contemporaries including Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler, who explicitly described Pfitzner's first string quartet (in D-Major) of 1902/03 as a masterpiece.

Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novella ...

praised ''Palestrina'' in a short essay published in October 1917. He co-founded the Hans Pfitzner Association for German Music in 1918. Tensions with Mann, however, developed and the two severed relations by 1926.

From the mid-1920s, Pfitzner's music increasingly fell in the shadow of Richard Strauss. His opera, ''Das Herz'' of 1932, was unsuccessful. Pfitzner remained a peripheral figure in the musical life of Nazi Germany, and his music was performed less frequently than in the late days of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

.

German critic Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt

Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt (1 November 1901 – 15 August 1988) was a German composer, musicologist, and historian and critic of music.

Life

Stuckenschmidt was born in Strasbourg. At as early an age as 19, he was the Berlin-based music criti ...

, writing in 1969, viewed Pfitzner's music with extreme ambivalence: initiated with sharp dissonances and hard linear counterpoint determined to be taken as (and criticized for being) modernist. This became a conservative rebellion against all modernist conformity. Composer Wolfgang Rihm

Wolfgang Rihm (born 13 March 1952) is a German composer and academic teacher. He is musical director of the Institute of New Music and Media at the University of Music Karlsruhe and has been composer in residence at the Lucerne Festival and the Sa ...

commented on the increasing popularity of Pfitzner's work in 1981:

Pfitzner is too progressive, not simply, the way Korngold can be taken to be; he is also too conservative, if that means to be influenced by someone like Schoenberg. All this has audible consequences. We cannot find the brokenness of today in his work at first glance, but neither the unbroken yesterday. We find both, that is, none, and all attempts at classification falter.

Students of Hans Pfitzner

* Sem Dresden (1881–1957) *Ture Rangström

Anders Johan Ture Rangström (30 November 1884 – 11 May 1947) belonged to a new generation of Swedish composers who, in the first decade of the 20th century, introduced modernism to their compositions. In addition to composing, Rangström was a ...

(1884–1947)

*Otto Klemperer

Otto Nossan Klemperer (14 May 18856 July 1973) was a 20th-century conductor and composer, originally based in Germany, and then the US, Hungary and finally Britain. His early career was in opera houses, but he was later better known as a concer ...

(1885–1973)

*W. H. Hewlett

William Henry Hewlett (16 January 1873 – 13 June 1940) was a Canadian organist, conducting, conductor, composer, and music educator of English birth.

Early life and education

Born in Batheaston, Hewlett was a Boy soprano, treble in the choir a ...

(1873–1940)

*Heinrich Jacoby

Heinrich Jacoby (1889–1964), originally a musician, was a German educator whose teaching was based on developing sensitivity and awareness. His collaboration with his colleague Elsa Gindler (1885–1961), whom he met in 1924 in Berlin, pl ...

(1889–1964)

*Czesław Marek

Czesław Marek (1891–1985) was a Polish composer, pianist, and piano teacher who settled in Switzerland during World War I.

Life

Born in the town of Przemyśl in Eastern Galicia, near Lwów (now Lviv in Ukraine), Marek studied in that ci ...

(1891–1985)

*Charles Münch

Charles Munch (; born Charles Münch, 26 September 1891 – 6 November 1968) was an Alsatian French symphonic conductor and violinist. Noted for his mastery of the French orchestral repertoire, he was best known as music director of the Boston ...

(1891–1968)

*Felix Wolfes

Felix Wolfes (September 2, 1892 in Hannover – March 28, 1971 in Boston) was an American educator, Conducting, conductor and composer.''Baker's Biographical Dictionary'', eighth edition, p. 2068

Biography

Felix was born to Jewish parents in Hanno ...

(1892–1971)

*Carl Orff

Carl Orff (; 10 July 1895 – 29 March 1982) was a German composer and music educator, best known for his cantata '' Carmina Burana'' (1937). The concepts of his Schulwerk were influential for children's music education.

Life

Early life

Carl ...

(1895–1982)

*Heinrich Sutermeister

Heinrich Sutermeister (12 August 1910 – 16 March 1995) was a Swiss composer, most famous for his opera '' Romeo und Julia''.

Life and career

Sutermeister was born in Feuerthalen. During the early 1930s he was a student at the Akademie der T ...

(1910–1995)

Recordings

His complete orchestral works have been recorded by the German conductorWerner Andreas Albert

Werner Andreas Albert (10 January 1935 – 10 November 2019) was a German-born Australian conductor.

Personal life

Albert was born in Weinheim. He began his studies in musicology and history, and later studied conducting with Herbert von Ka ...

. His complete songs have been recorded on the CPO label. Also, his chamber music, including 4 string quartets, 2 piano trios, a violin sonata, a couple of odd piano works, a piano quintet and a string sextet, and a cello sonata have been recorded several times.

Works

Operas

Orchestral works

Chamber works

Instrumental works

Choral works

Songs with piano accompaniment

References

Notes Further reading * * *External links

*UbuWeb:A New Musical Reality": Futurism, Modernism, and "The Art of Noises"

by Robert P. Morgan * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Pfitzner, Hans 1869 births 1949 deaths Burials at the Vienna Central Cemetery German male conductors (music) German male classical composers German opera composers German Romantic composers Hoch Conservatory alumni Male opera composers Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) 20th-century German conductors (music) 20th-century German male musicians 19th-century German male musicians Pupils of Iwan Knorr